Introduction and Motivation

The contents of this post are predominantly based on the review paper by Otter et al. 1 which discusses the computational aspects of Persistent Homology (PH). To begin with, the first four sections of the paper give a very good introduction to TDA without getting lost in unnecessary mathematical details. I believe that this can serve as a first introduction to PH for anyone who later wishes to understand PH with proper mathematical rigor. However, in the current post, I would like to focus on the first half of section five which familiarizes the reader with some of the simplicial complexes used while working with point-cloud data.

TDA deals with data that can be viewed as finite metric spaces. Such data sets are also referred to as point-cloud data sets. For instance, networks and digital images can be modeled as finite metric spaces. The lecture notes by Prof. Vidit Nanda2 were extremely helpful in learning some basics of computational topology. The article by Lazar and Ryu3 does a really good job of giving the big picture for TDA. Now, given a finite set of points, we wish to encode the “shape” information of the data into a simplicial complex which is much easier to handle mathematically. Simplicial complexes give us the benefit of exploiting the well-understood field of simplicial homology which is known to be better in terms of computations.

Notations used in the post: Let $S$ be the finite dataset (also a metric space) at hand. $K$ is the simplicial complex on vertex set $S$ with $|S| = n < \infty$. Note that $\sigma = \langle v_{j_0}, \cdots, v_{j_p}\rangle$ denotes a $p$-simplex in $K$ i.e. $\sigma$ is the convex hull associated with the vertices $\lbrace v_{j_0}, \cdots, v_{j_p} \rbrace \subset S$. We use the notation $K_i$ to denote the set of all $i$-dimensional simplices in $K$. We assume that the data set $S$ lies inside an unknown metric space $(X,d)$ such that $(S,d)$ is an induced metric space.

A finite cover of a topological space, given by $\mathcal{U} = \lbrace U_s \rbrace_{s \in S}$, defines a special simplicial complex $N(\mathcal{U})$ called the Nerve of $\mathbf{\mathcal{U}}$ as follows:4

\[N(\mathcal{U}) = \left\lbrace \langle v_{j_0}, \cdots, v_{j_p}\rangle : \lbrace v_{j_0}, \cdots, v_{j_p}\rbrace \subseteq S \text{ and } \bigcap_{z=0}^p U_{j_z} \neq \emptyset \right\rbrace\]Big picture: Persistent homology is a tool that allows the encoding of shape information at different scales. At each scale value, we need to store the shape information in the form of a simplicial complex. Finite metric spaces are not topologically interesting5, hence we try to “fill in the gaps” between data points if they are “close enough” in some sense. That way we will be able to impose topological structures onto the data.6 The idea is that if we build a simplicial complex $K$ on set $S$, then the homology of $K$ has to at least ``approximate” the homology of $X$. Hence the choice of how to construct the simplicial complex matters.

$\check{\mathcal{C}}(S; \epsilon)$: Cech complex at scale $\epsilon > 0$

Given a fixed positive $\epsilon \in \mathbb{R}$, the Aleksandrov-Cech complex, also commonly known as the Cech complex, at scale $\epsilon$ is defined as the intersection complex or nerve of the $\epsilon$-balls associated with set $S$. The resource Cech Complex playground is a useful visualization tool. The Cech complex, denoted by $\check{\mathcal{C}}(S, \epsilon)$, is defined as follows:

\[\check{\mathcal{C}}(S; \epsilon) = \left\lbrace \langle v_{j_0}, \cdots, v_{j_p} \rangle \subset S \quad : \quad \bigcap_{z=0}^p \mathcal{B}(v_{j_z}; \epsilon) \neq \emptyset \right\rbrace\]The Nerve Lemma provides a theoretical guarantee on why the Cech complex is “correct”. There are different versions of the Nerve Lemma, but all of them have a similar idea which is given below7.

Let $\mathcal{A} = \lbrace A_1, \cdots, A_m \rbrace$ be a family of “nice” subsets covering a space Euclidean $X$ such that all possible intersections are “topologically simple”, then the topology of the nerve agrees with the topology of $X$ in certain ways. Despite the advantage of the Nerve Lemma, the Cech complex is not widely used due to a lack of computational feasibility.

Assume $|S| = n$, then the worst case size (i.e. cardinality of the set $K$) of the simplicial complex associated with data is $\mathcal{O}(2^n)$. The number of steps required to associate the data to a simplicial complex is also $\mathcal{O}(2^n)$ since we have to check the intersection of all possible collections of simplices in $K$.

$\mathcal{VR}(S; \epsilon)$: Vietoris-Rips complex at scale $\epsilon > 0$

When homology theory was still new, Leopold Vietoris used a complex that is similar to the Vietoris-Rips complex to model metric spaces using finite simplicial complexes. The Vietoris-Rips complex, often called the Rips complex, is now commonly used in TDA due to its computational benefits over the Cech complex. The Rips complex associated with the dataset $S$ is defined as follows:

\[\mathcal{VR}(S; \epsilon) = \left\lbrace \sigma \subseteq S \quad : \quad \mathrm{d}(x,y) \leq 2\epsilon \quad \forall x,y \in \sigma \right\rbrace\]Given any $\epsilon > 0$, the Rips complex is said to approximate the Cech complex because the Rips complex at scale $\epsilon$ can be “sandwiched” between Cech complexes at scales $\epsilon$ and 2 $\epsilon$. These bounds cannot be improved if $X$ is assumed to be an arbitrary metric space. The upper radius can be improved to $\frac{\sqrt{3}\epsilon}{2}$ if the underlying space $X$ is Euclidean.6

\[\check{\mathcal{C}}(S; \epsilon) \quad \subseteq \quad \mathcal{VR}(S; \epsilon) \quad \subseteq \quad \check{\mathcal{C}}\left(S; \frac{\sqrt{3}\epsilon}{2} \right) \quad \text{ when underlying metric space is Euclidean}\]Assume a $p$-simplex $\sigma \subseteq S$ with $|S| = n$, the following are the computational costs associated with Rips and Cech complexes:

- In order to construct $\check{\mathcal{C}}(S; \epsilon)$, we have to check all possible $k$-set intersections for $k = 1,2, \cdots, n$. Observe that there are $n \choose k$ many subsets of $S$ of size $k$. Hence there are $n \choose k$ many intersections that need to be checked. This implies that Cech complex construction takes exponential time. On the other hand, it is sufficient to check all possible pairwise intersections to construct the Rips complex. This clearly takes polynomial time.

- However, the cardinality of the Cech complex or Rips complex is still exponential. This is because the worst case complex is $\mathcal{P}(S)$, powerset of $S$, in either of the two cases. Hence one usually computes the Rips complex up to some dimension $p « n$.

Rips complex construction

- Compute the proximity graph or $\epsilon$-neighbourhood graph, denoted as $N_{\epsilon}(S)$, associated to the dataset $S$. This will be a graph $N_{\epsilon}(S) = (S, \mathcal{E})$ with edge set $\mathcal{E}$ defined as

- Rips complex is the clique complex associated with the proximity graph $N_{\epsilon}(S)$. A clique complex, also referred to as the flag complex, associated with the graph $N_{\epsilon}(S)$ is defined by adding simplices as follows:

Despite the computational benefits, one of the major drawbacks of the Rips complex is that we do not have Nerve Lemma-like theoretical guarantees. However, a couple of weaker results can be found in the lecture notes by Prof. Jeff Erickson.6

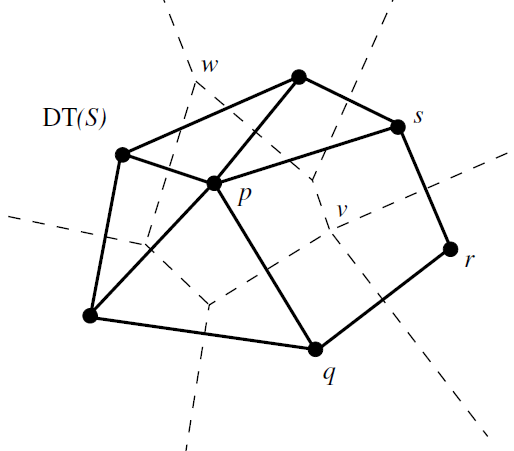

$\mathrm{Del}(S, \mathbb{R}^d)$: Delaunay complex

Delaunay complex is a sparse complex i.e. it does not contain “too many” simplices. Observe that even though the Rips complex construction takes polynomial time, the size of the Rips or Cech complex is still exponential which can be very difficult to handle in practice.4 This forms a simple motivation to search for complexes that are “sparse”. For now, we assume $X = \mathbb{R}^d$.

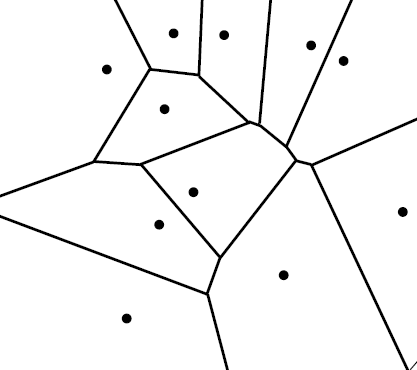

There are two equivalent ways of defining the Delaunay complex - one involves the Voronoi Diagram of the data set $S$ and the other is more abstract but becomes more understandable once we understand the first definition. 8 The Delaunay complex of a finite set $S$ is the nerve of the Voronoi diagram of $S$. Let $S = \lbrace s_1, s_2, \cdots, s_n \rbrace \subset \mathbb{R}^d$ be a set with $n$ distinct points. The define the Voronoi cell of $s_i$, $\mathcal{V}(s_i, S)$, as the locus of all points in $\mathbb{R}^d$ that is closest to $s_i$ than any other $s_j$ for $j \neq i$.

\(\mathcal{V}(s_i, S) = \left\lbrace x \in \mathbb{R}^d : \lvert \lvert x - s_i \rvert \rvert \leq \lvert \lvert x - s_j \rvert \rvert \quad \forall s_j \in S-\lbrace s_i \rbrace \right\rbrace \ = \bigcap_{j \neq i} \lbrace x \in \mathbb{R}^d : \lvert \lvert x - s_i \rvert \rvert \leq \lvert \lvert x - s_j \rvert \rvert \rbrace\)

Observe that the Voronoi cells form a cover for the underlying space in such a way that the interiors of these cells are pairwise disjoint.

\[\mathbb{R}^d = \bigcup_{i=1}^n \mathcal{V}(s_i, S) \quad \text{ such that } \quad \mathrm{Int}(\mathcal{V}(s_i, S)) \cap \mathrm{Int}(\mathcal{V}(s_j, S)) \text{ for } i \neq j\]The collection of Voronoi cells $\lbrace \mathcal{V}(s_i) \rbrace_{i=1}^n$ and their faces constitute the Voronoi Diagram of $S$, denoted as $\mathcal{V}(S)$. Nerve of the cover associated with this diagram gives the abstract simplicial complex called Delaunay Complex.

Mathematical structure of $\mathcal{V}(S)$

The Voronoi diagram of $S$ is a mathematical structure called Cell Complex which can be thought of as the generalization of a simplicial complex. 8 Observe that a simplicial complex $K$ is made of simplices which are all, in general, said to be the faces of $K$. Similarly, a cell complex $C$ is made up of “special” faces that satisfy the properties that the simplices in $K$ satisfy. Let $f, g \in C$, then

- Any face of $f$ is a face of $C$.

- $f \cap g = \emptyset$ OR $f \cap g$ is a common face of both $f$ and $g$.

The “specialty” of these faces is that each one is a closed convex set called convex polyhedron, which can be viewed as a generalized simplex. However, unlike (finite) simplices, convex polyhedra may or may not be bounded. Another way of adding simplices to the Delaunay complex (other than the nerve definition), is by using the Empty ball property.

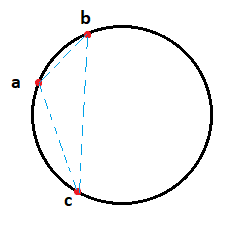

Lemma (Empty ball property)8 Any subset $\sigma \in S$ is a simplex in $\mathrm{Del}(S, \mathbb{R}^d)$ iff it has a circumscribing ball $\mathcal{B}$ with no points of $S$ in the interior of $\mathcal{B}$.

Using the above lemma, the following is an alternate way of defining the Delaunay complex.

A $p$-simplex $\sigma$ is said to be Delaunay if the vertices of $\sigma$ lie in $S$ and there exists an open ball $\mathcal{B}$ satisfying the following conditions:

\[S \subseteq \partial \mathcal{B} \text{ and } S \cap \mathrm{Int}(\mathcal{B}) = \emptyset \text{ where } \mathcal{B} = \partial \mathcal{B} \sqcup \mathrm{Int}(\mathcal{B})\]Remark: $\partial \mathcal{B}$ and $\mathrm{Int}(\mathcal{B})$ denote the boundary and interior of $\mathcal{B}$ respectively while the symbol $\sqcup$ refers to disjoint union of sets. Given a Delaunay simplex $\langle v_0, \cdots v_p \rangle$ for $p \leq d$, we can visualize it as $p+1$ points lying on the surface of a sphere in $\mathbb{R}^d$. Below is the example of a case that is easy to draw: Consider $p=d=2$ i.e. we have a $2$-simplex $\langle a, b, c\rangle$ in $\mathbb{R^2}$ which is Delaunay.

Then, the Delaunay complex associated with $S$ is defined as:

\[\mathrm{Del}(S, \mathbb{R}^d) = \lbrace \sigma : \sigma \in S \text{ and } \sigma \text{ is Delaunay } \rbrace\]What is “nice” about the Delaunay Complex?

Given the definition of Delaunay simplices, it is natural to wonder if the Delaunay complex can exist for a specific dataset $S$. If it exists, what theoretical guarantees or benefits does it provide? The facts mentioned below4, summarize without proof, the “niceness” of Delaunay complex in certain scenarios:

- Every non-degenerate point set9 $S$ in $\mathbb{R}^d$ admits a unique Delaunay complex.

- Points in $S$, with $\lvert S\rvert = n$, are said to be in general position w.r.t. spheres if no $d+2$-size subsets of $S$ lie on the same hypersphere10. This ensures that $\mathrm{Del}(S, \mathbb{R}^d)$ can be embedded in $\mathbb{R}^d$.

Theorem: If points in $S$ are in general position w.r.t spheres, then $\mathrm{Del}(S, \mathbb{R}^d)$ has a natural embedding in $\mathbb{R}^d$. This embedding is a triangulation of $S$ called the Delaunay triangulation of $S$. This triangulation can be proved to be “optimal” in certain ways.4

Comparing Delaunay with Cech/Rips

One of the most fundamental assumptions in TDA is that the underlying space $X$ from which data $S$ is sampled has the topological property that they can be triangulated. Intuitively, this means, the object’s shape from which data is obtained can be approximated using a simplicial complex. Now, the next natural question is - Which simplicial approximation do we choose and how? This can be dealt with in two different ways:

- In the case of Cech/Rips, there exists a scale parameter $\epsilon$ which determines how refined our simplicial approximation is. Instead of looking at the “best” epsilon, we look at a sequence of simplicial approximations and try to observe how the topology changes with a change in the $\epsilon$ value.

- While working with Delaunay, the output we get is a particular triangulation or simplicial approximation which is the “best” in certain ways.

Limitations

Due to the different optimal properties listed in the textbook by Dey and Wang4, this complex is used mostly while working with $X = \mathbb{R}^2$ or $\mathbb{R}^3$. However, computations in $\mathbb{R}^d$ for $d \geq 4$ are time intensive and hence not yet a widely used complex in higher dimensions.

Note: Prof. Peter Bubenik’s website11 has some useful R resources for TDA. In particular, it has an R worksheet on how to generate Voronoi diagrams and Delaunay complexes.

Alpha Complex

Witness complex

-

Otter, N., Porter, M.A., Tillmann, U. et al. A roadmap for the computation of persistent homology. EPJ Data Sci. 6, 17 (2017). ↩

-

Computational Algebraic Topology, Lecture notes by Prof. Vidit Nanda, Mathematical Institute, University of Oxford. ↩

-

Nicole Lazar & Hyunnam Ryu (2021) The Shape of Things: Topological Data Analysis, CHANCE, 34:2, 59-64, DOI: 10.1080/09332480.2021.1915036 ↩

-

Dey, T., & Wang, Y. (2022). Computational Topology for Data Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5

-

A finite topological space is metrizable iff it is discrete, Math StackExchange ↩

-

Nov 11 notes under “Complexes and Homology”, CS598: Computational Topology (Fall 09), Lecture notes by Prof. Jeff Erickson, Dept. of Computer Science, UIUC, Viewed on 06/27/2023. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

(2008). A Topological Interlude. In: Using the Borsuk–Ulam Theorem. Universitext. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. ↩

-

Boissonnat, Jean-Daniel, Frédéric Chazal, and Mariette Yvinec. 2018. Geometric and Topological Inference. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Non-degenerate point set, Math StackExchange ↩

-

Weisstein, Eric W. “Hypersphere.” From MathWorld–A Wolfram Web Resource. ↩

-

Peter Bubenik’s TDA resources, Dept. of Mathematics, University of Florida ↩